Hidden Gems Exhibition

A new exhibition at Leicester Museum & Art Gallery highlights some of the hidden gems from the Museum's geology collection.

Published: 1 October 2024

Since February 2024, a group of volunteers have been working alongside the Museum's Collections Team to study and record thousands of rocks, fossils, and minerals at Leicester Museum and Art Gallery. This is part of our constant behind-the-scenes work which ensures that the geology collection is properly documented.

Five of these volunteers have chosen their favourite specimens from the project and have written about them in their own words. These hidden gems are now on show at Leicester Museum and Art Gallery.

Pink Barite chosen by Gemma

The high temperatures and pressures that affect minerals, metals, and other elements within the earth to produce crystals have always fascinated me. I loved seeing the specimens in the museum collection, my favourite being the pink barite. Pink barite has a dusky pink hue, like rose gold. It is heavily textured giving it a wild and windswept look. I am left in wonder at the magic of nature.

Gallery

Gypsum chosen by Helen

I was drawn to gypsum because of the colour. Pink gypsum is used in building construction, soil fertiliser and it was even used as a replacement for wood in the Bronze Age when the material was scarce. There are different forms of gypsum including alabaster which the Ancient Egyptians used for sculpture. Alabaster was also used in the Midlands as in the Medieval period it was used in Nottingham where they made altar pieces for churches which could not afford marble.

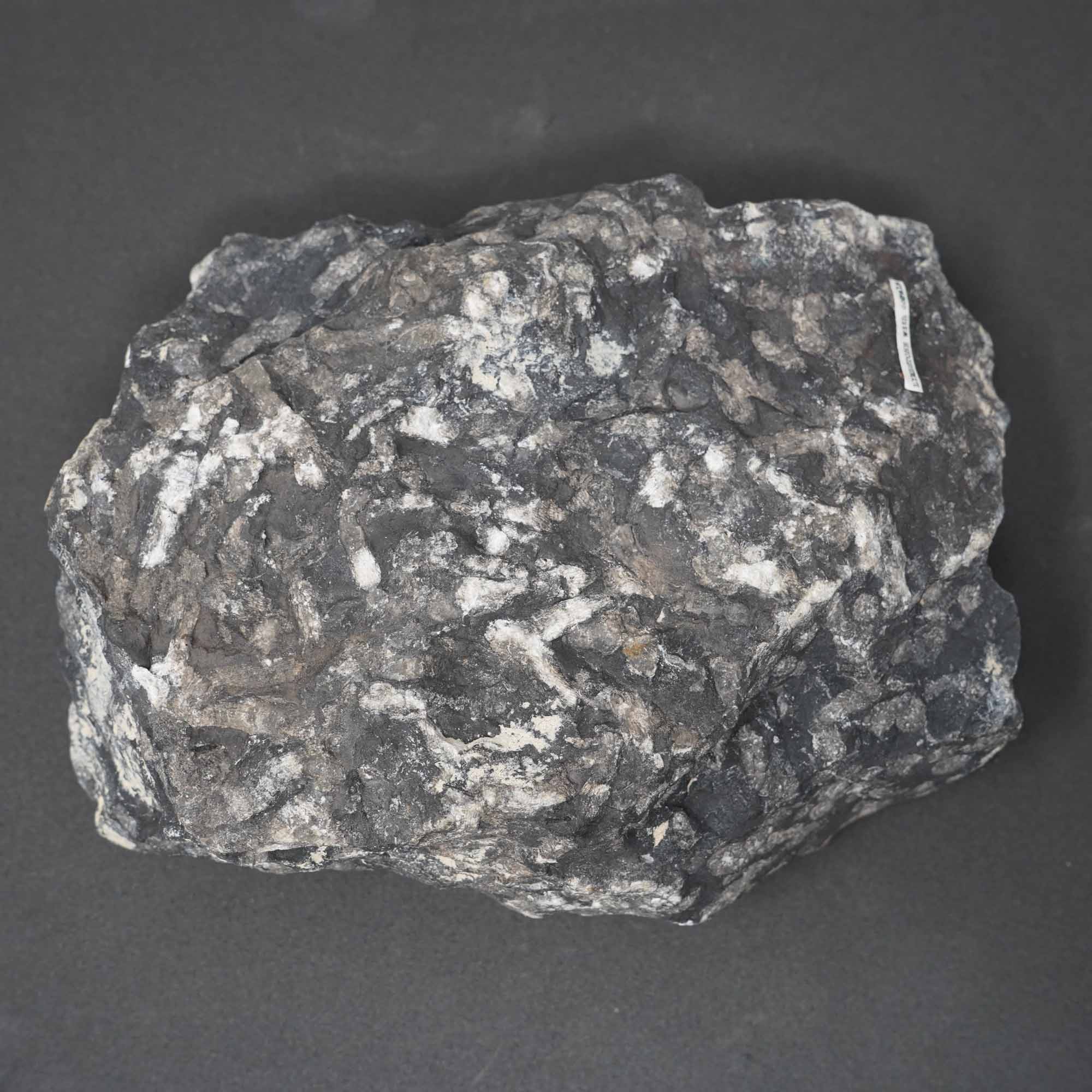

Triassic Bone Bed chosen by Chris

This rock is part of the Westbury Bone Bed, representing a lagoonal environment full of vertebrate life during the Rhaetian of the late Triassic, about 201 million years ago. The lagoonal conditions ended almost 100 million years of arid desert conditions within the UK from the Permian to Triassic. Several bone fragments are visible, and would have been the remains of marine reptiles inhabiting this lagoon, all disarticulated by the stormy conditions which the rock was deposited in. The small black pebbles are the phosphatised remains of coprolites, fossilised digested remains.

Together, these organisms would have swum alongside the recently discovered Ichtyotitan severnensis, a 25m titan ichthyosaur from the same time period and environment, plesiosaurs, hybodont sharks, and large predatory fish. The brass-coloured metallic crystals are pyrite, and indicate conditions devoid of oxygen as the rock began to fossilise and become part of the geological record.

Gallery

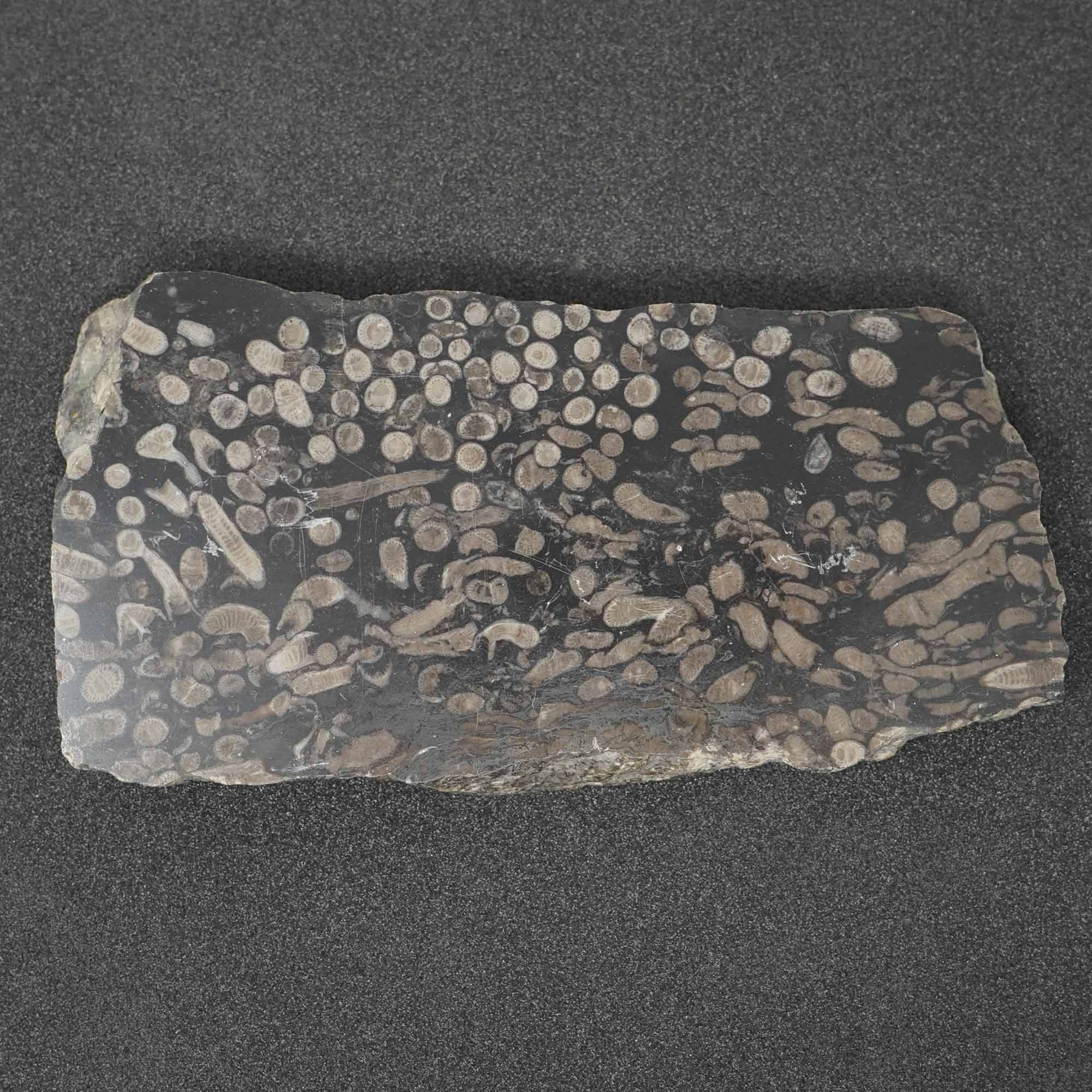

Frosterley Marble chosen by Avaneesh

Picture this. 325 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period, a Bahamas-like-scene with creatures swimming about in a coastal paradise. Corals, goniatites, brachiopods, forams, crinoids, bryozoans, and algae; various forms of ancient lineages thrived in this coastal abode. Only a few remnants of these species survive today. Funnily enough, the traces of this scene aren’t on any far-off coast, but are found buried deep in Durham!

A trickery in the naming of the rock calls for it to be a marble, but it’s actually a black limestone. A polished surface gives it an extravagant look. The white tubes and circles with tabulations inside belong to the coral species Dibunophyllum bipartium. These creatures looked like conical horns hooked onto the seabed, using their tentacles to filter feed organic matter present in the seas. After their death they tended to collect as skeletons, layers upon layers, covered up by precipitating limestone and anoxic conditions, painting on a darker shade to the matrix.

Just like corals, you can find many more of the previously mentioned organisms as well, locked away in millennial scale cycles of deposition. Today you can find these rocks used as walls, tombstones, and pillars, mainly in places of great importance such as the Cathedrals at Durham and Peterborough. A tale of a magnificent shallow marine ecosystem locked away in rock, and two of its fragments lie here, at Leicester Museum, for future Palaeontologists and Geologists to study.

Gallery

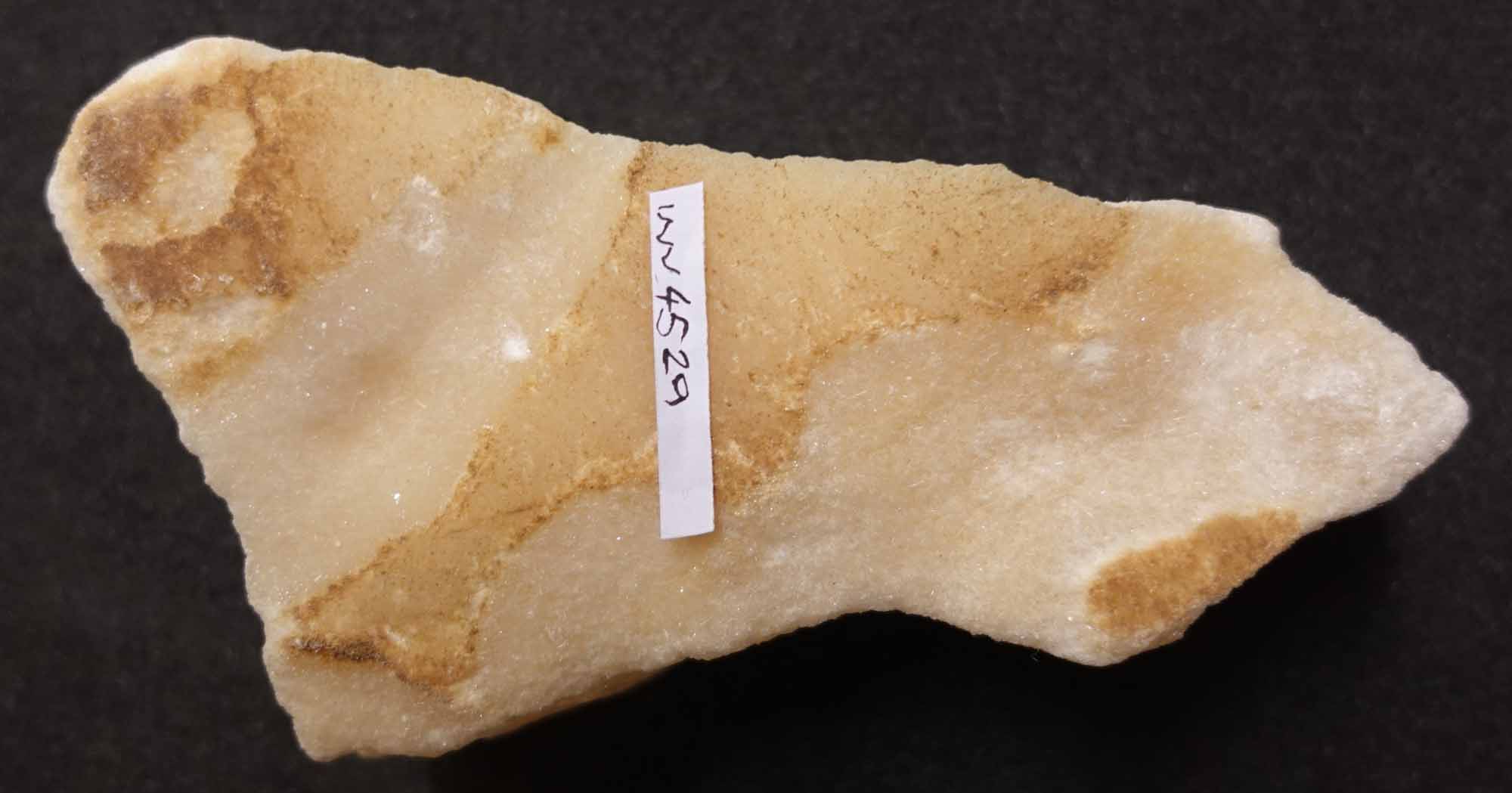

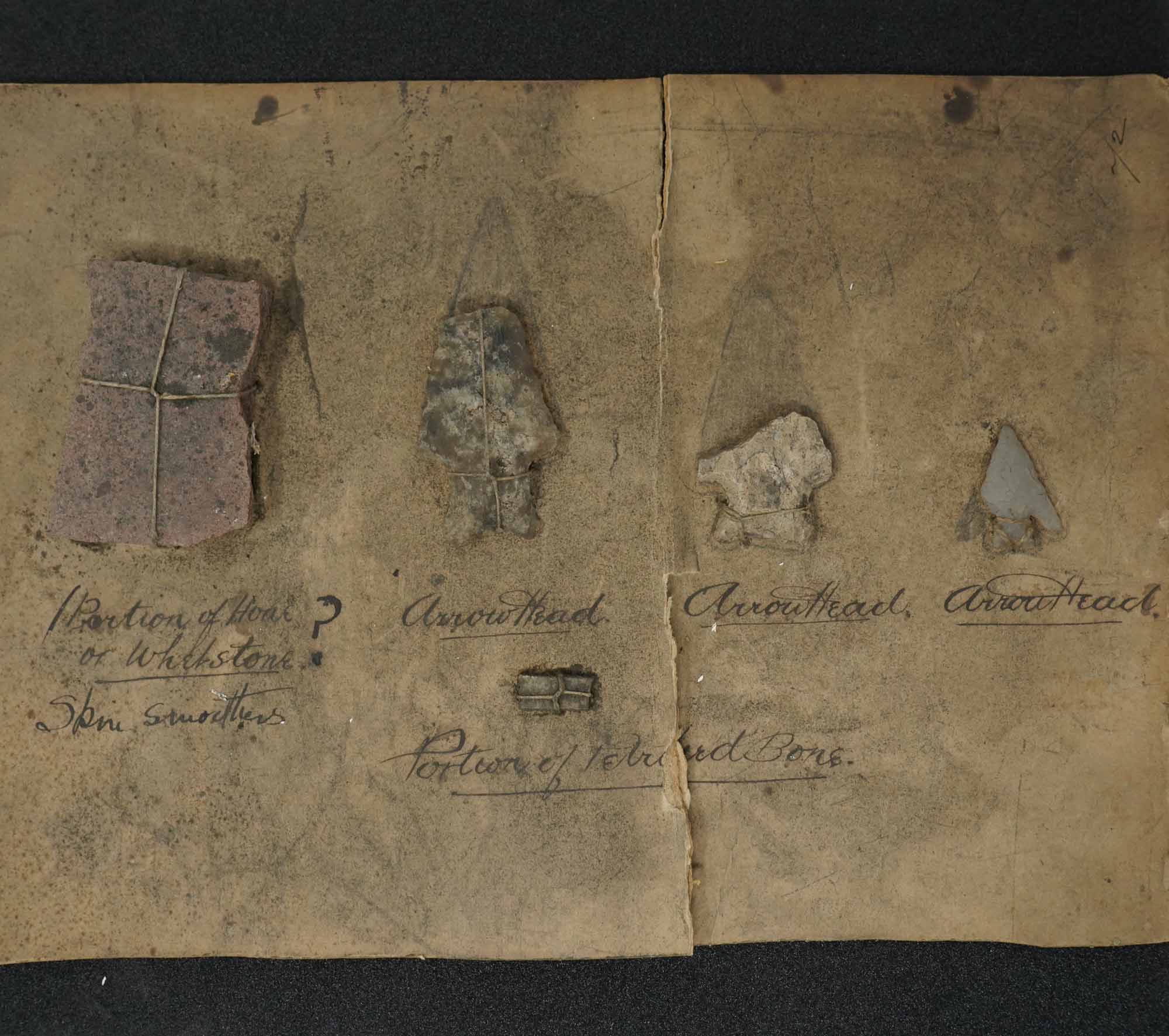

Neolithic Axe and Arrow Heads chosen by Freddy

I have thoroughly enjoyed my time documenting geology specimens for Leicester Museums. My favourite specimen was a collection of Neolithic flint axe heads; there was something thought provoking about the journey these tools had been on. Their origins as an instrument for someone to help survive, being preserved in the ground for centuries and their journey from an archaeology dig to the Museum archives, all told through a small box full of flint tools. Overall, I recommend anyone who has an interest in how museums work behind the scenes to volunteer at Leicester Museum and Galleries.

Gallery

Images credited to: Maya Sylvia.