Global Leicester: Wiener Werkstatte

Published: 7 October 2021

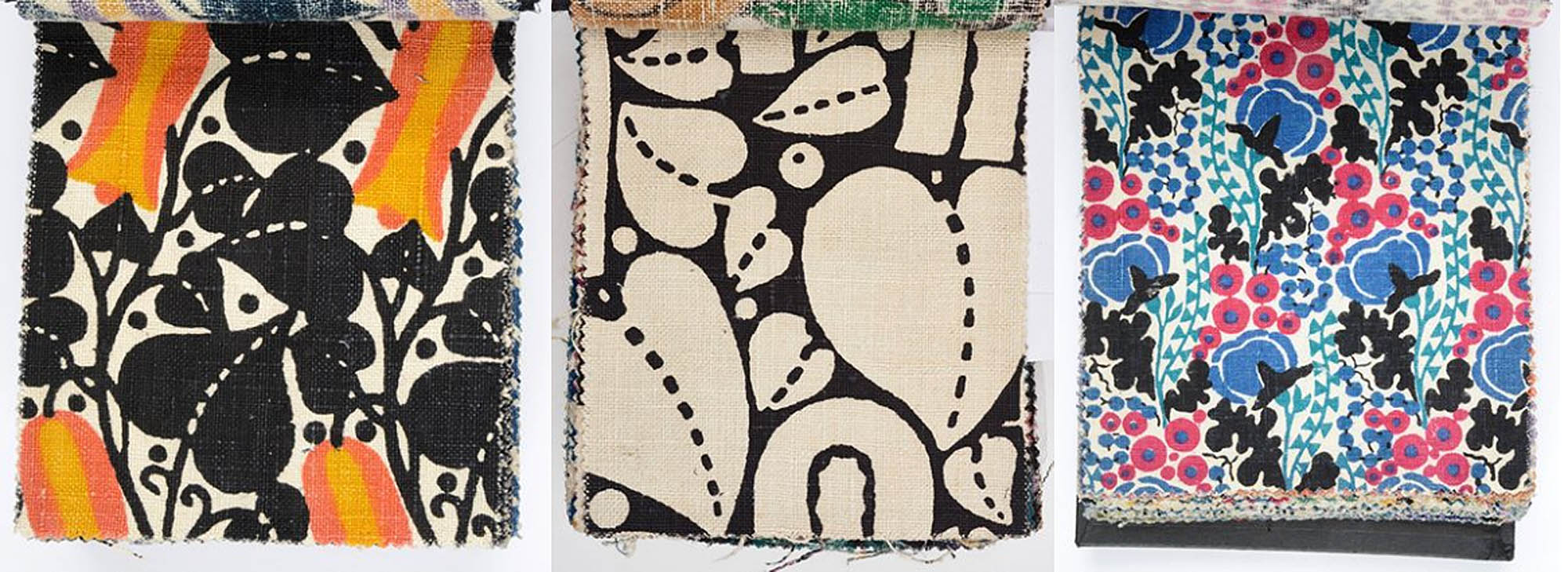

Fabric samples from Wiener Werkstatte © MAK Museum in Vienna

In 1903, in the context of late imperial Vienna, the architect Josef Hoffmann, the painter Koloman Moser and the industrialist Frits Waerndorfer founded the Wiener Werkstätte, whose programme aimed to elevate every aspect of daily life through excellent craftmenship and design. This led to the development of workshops for furniture, jewelry, metal objects, fashions and pottery. We are in the midst of a period of design reform involving all Europe, and based on new ideas about the importance of functionality and materials.

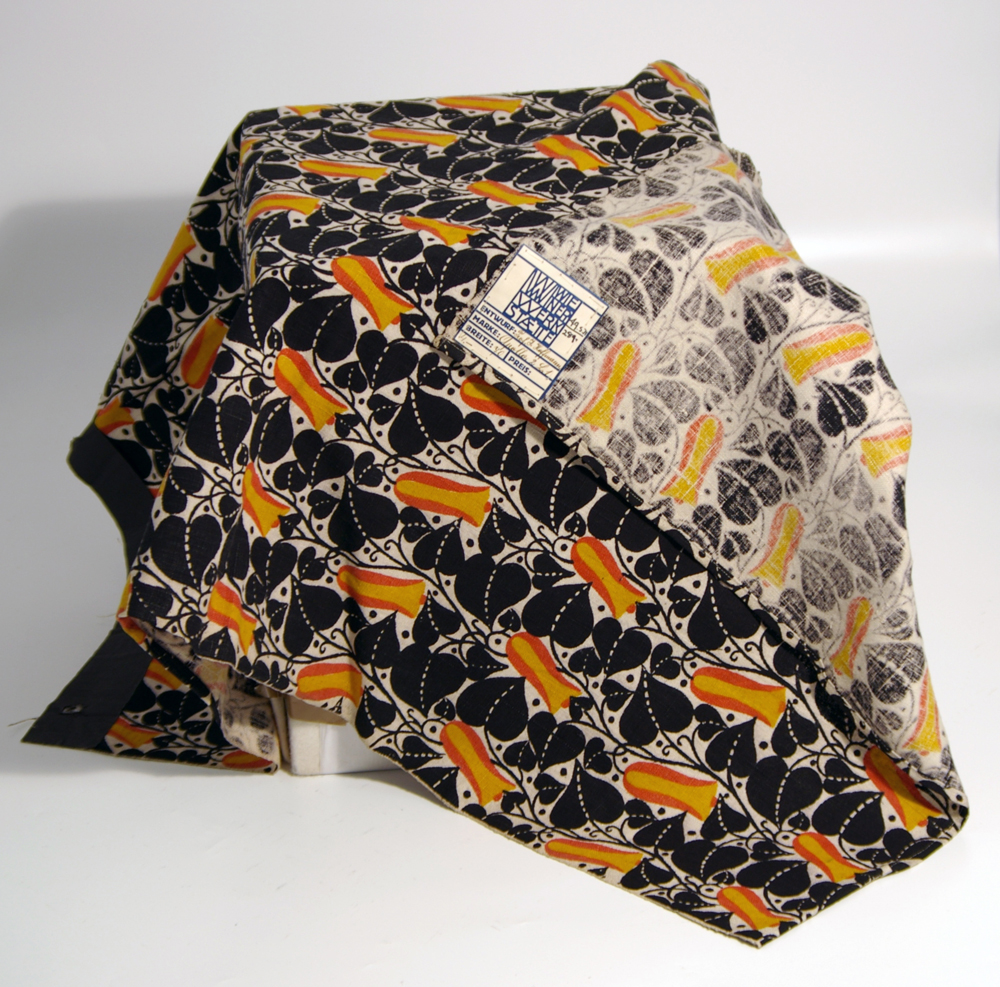

The Dryad collection contains eleven samples of linen fabrics from the Wiener Werkstätte. How Harry Peach gathered those pieces? And why was he interested in Wiener Werkstätte? To clarify this aspect, I visited the Museum für angevandte Kunst (Museum of Applied Arts) in Vienna, which is part of the University of Applied Arts, and held the most important archive of Wiener Werkstätte. This allowed me to analyse the collection of textiles, to understand their international circulation, and to develop hypothesis on how some of them travelled to Leicester. The Museum für angevandte Kunst contains diverse fabrics in terms of patterns and materials, ranging from big linen samples to cottons, silks, and oddments of different shapes. You easily risk getting lost in beautiful details and colours if you do not know what you are looking for. My idea was to understand what the life of those textiles was before they entered the museum, what were the places of commerce and exchange, and therefore how Harry Peach was capable to purchase and take them to Leicester.

Wiener Werkstatte Gallery

Textiles were manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte from 1905 on, mainly hand printed. Showrooms, shops, and exhibitions were the places where it was possible to admire these textiles. While the first Wiener Werkstätte shop dedicated to fashion and textiles opened its door in 1910, examples from the Wiener Werkstätte textiles have been exhibited in a number of exhibitions and trade fairs that have taken place all over Europe, especially in Germany (1). Among them, the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne, where the Wiener Werkstätte had its own pavilion, the 1925 Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, and the 1927 Leipzig European Exhibition of Arts and Crafts. Peach was a regular visitor of international exhibitions in Europe, and he visited the three mentioned, playing a central role in Leipzig to organise the British pavilion (2). For this reason, I considered the hypothesis that Peach purchased his Wiener Werkstätte textiles in these events. However, in the exhibitions’ catalogues there is no mention of the eleven pattern samples that arrived in Leicester.

By questioning the ‘sales policy’, I found out that the Museum für angevandte Kunst has three types of fabric sample books, which displays a range of printed linens and silks. These are books whose pages are made by fabric which measure around 15 x 20 cm, in order to show the patterns in a contained space. Given the lack of space in the established retail premises, Angela Völker sustains that sellers simply showed these oddments to customers, so that “not only could each customer obtain an overall view of the available fabrics in this way, but representatives were also supplied with sample books in order to be able to give wholesalers, other branches or any commissioning body a comprehensive idea of the fabric production” (3).

Interestingly, two linen sample books at the Wiener Werkstätte archive contain each of the eleven patterns of the bigger linens in Leicester! Also, the books dated before 1914, and the design of the linens in Leicester suggests a production during the early 1910s. This ‘match’ could mean that Peach purchased his fabrics from a private individual during a trip to Vienna. There are a total of 104 different pattern samples in the two books, but I do not know why Peach chose these eleven and excluded the others. I can say that an obsession for patterns is a constant presence in the Dryad collection. In fact, figures are very rare, while simple and geometric decorations are much more sought after not only in textiles, but also in painted wooden objects, ornaments on shells and coconut, stitching on wicker and basketwork. This is a Fil Rouge in the entire collection, and one of the main elements around which I am developing new questions for my research and new hypothesis for the accumulation of certain objects.

Maria Chiara Scuderi

(1) The first publication on the history and production of the Wiener Werkstätte was Werner J. Schweiger, (1984). Wiener Werkstätte. Design in Vienna 1903 – 1932, London: Thames and Hudson. After this, a number of publications followed, and Angela Völker is the author who wrote most extensively on textiles and wallpaper design: Angela Völker, (2004). Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte 1910 – 1932, New York: Thames and Hudson; Angela Völker, (2017), The Unknown Wiener Werkstätte: Embroidery and Lace 1906 to 1930, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts: Arnoldsche.

(2) Notes on visit to the Leipzig International Exhibition of Modern Applied Art, Germany, 1927. RIBA Drawings & Archives Collections, PeH/1/2, paragraph: 1.18.

(3) Angela Völker, (2004). p. 163.

Learn more about Harry Peach and the Dryad Collection on our Arts & Crafts website